Execration. It’s the more precise term for ‘curse.’ It comes from the Latin word “execrare.” “Ex” meaning “out” (as in exterior) and “sacrare” meaning to make sacred (as in consecrate.)

Tomb curses

The most famous ancient Egyptian curse is the one on King Tutankhamen’s tomb. The excavators ignored the warning: “Death shall come on swift wings to him that toucheth the tomb of a Pharaoh.” However, the whole story was a hoax. There is no such inscription anywhere in the tomb, though the reputed curse text may have been a mis-translation of spell 151 of the Book of the Dead, or the text found on one of the magic bricks. One of the original security officers from the dig also said in a 1980 interview that they had deliberately circulated stories about a curse to discourage thieves.

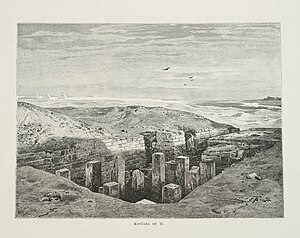

Tomb curses are rare, possibly because the Egyptians didn’t like to put negative things in tombs for fear of giving power over the owner. Hieroglyphs for birds and other animals were ‘maimed’ in Old Kingdom tomb inscriptions, so the animals couldn’t cause trouble in the afterlife. Perhaps acknowledging the possibility of a robbery could have made it more likely. There are some tomb curses, including ones that threaten the paid Ka-priests if they failed to adhere to the agreed-upon offering contracts.

The 6th-dynasty mastaba tomb of Herymeru has this inscribed on the lintel:

“I am an excellent Akh, one who knows things, a speaker of perfection and a repeater of perfection. I have never said or done any evil thing in relation to anyone, for I am one who loves Ma’at, in the sight of the perfect God and in the sight of men.

But with regard to any man who shall do anything evil to my tomb, or who shall enter it with the intention of stealing, I shall seize his neck like a bird’s, and I shall be judged with him in the court of the Great God.

However, with regard to any person who shall make invocation offerings or shall pour water, they shall be pure like the pureness of god, and I shall protect him in the necropolis.”

A similar ‘contractual’ agreement is found on the offering table of Khentika Ikhekhi:

An offering which the king and Anubis, who is on his mountain, give to the imakhu, the overseer of the office of the khenty-she of the Great House Ishetmaa.

With regard to any Ka-priest of the sole companion Khentika, who shall not make the invocation offerings, I shall make him lose his job.

The overseer of the office of Khenti-she of the Great House Ishetmaa. A thousand of bread, beer, cakes, alabaster, clothing, incense. A thousand of five types of fowl for Ishetmaa.

Only a few later-era tombs had dire warnings, including at least one asking Sekhmet to cause a disease no doctor could diagnose! I wonder if one of the reasons why these curses weren’t used more is that they were obviously ineffective. Tomb-robbing seems to have been a practice that dates back to within hours of the tombs being sealed.

The other problem is that it does the tomb-owner no good if the thieves get away with all the treasures only to be struck down days, months, or years later. The treasures were still gone. Too bad they hadn’t seen the Indiana Jones movies. 😉

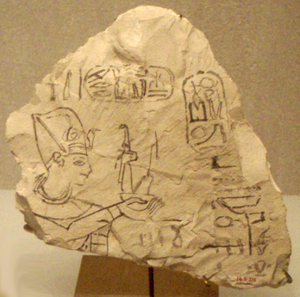

Execration Texts

Political cursing- execrating the enemies of Kemet, foreign and domestic, dates back to the Old Kingdom, and was an important pillar of royal Heka practice. The names of foreign countries, kings, and tribes, as well as unnamed ‘rebels’ within Egypt were written on pottery or statues. Then the items were broken as part of a ceremony and buried. Destroying the names of the enemies caused them harm. Wax figurines or drawings on papyrus got the same treatment.

Kemetic Voodoo Dolls?

Kemetic Voodoo Dolls?

The Egyptian figurines with accompanying nails or needles are instantly recognizable as ‘voodoo dolls‘ of popular fiction. The magician identifies a doll as a specific person, and sticks needles in it to give the target of this spell excruciating pain through sympathetic magic, the same principle used for the pottery-breaking execrations.

However, these dolls aren’t quite what they seem. In fact, they were used for love spells! The would-be lover would pierce the doll with copper needles saying “I pierce the eyes of (name) so she will not look at anyone but me. I pierce the mouth of (name) so she will not speak to anyone but me…” A lead tablet with inscriptions calling on deities or netjeri would be tied to the figurine with 365 knots, and the whole thing would be buried near the grave of someone who had met an untimely death.

The figures of women usually had their hands and legs bound behind them, and those of men held swords. It might be considered a curse to fall in love with someone obsessive enough to perform these rituals!

Modern Execration

Eternal Egypt by Richard Reidy contains three different execration rituals, all from the Bremner-Rhind papyrus (4th. c. BCE.) Two of them concentrate on the felling of Apep, and the third is directed at the earthly foes of Ra. I’ve done a couple execrations from this book. One was for a project of the Pagan Religious Rights group on Facebook. A Christian Dominionist group was doing prayer-curses against non-Christian influences in the US, state-by-state. The pagan group performed a ‘return to sender’ reflection of the curses, and I adapted the ‘Foes of Ra’ ritual to use for it.

From what I’ve observed, execrations in Kemetic Orthodoxy are not done against people. I’ve seen several which involved identifying a negative aspect of your life, like ‘procrastination,’ writing it down, and destroying the paper. The Wep Ronpet (Kemetic New Year) celebration in the Summer also involves destroying Apep in the form of a cake, or a drawing on paper, and I participated in an online version of it.

Black Magic?

Many pagans avoid doing any ‘negative’ magic, following the Wiccan Rede or a similar code. Looking at ancient Egyptian practice, it’s clear that no such proscription was in effect, with execrations performed by the Pharaoh and priests.

I’ve come to think of execrations as being a necessary part of Ma’at-as-balance. It’s not enough to use heka to support the positive things in the world. The negative needs to be actively resisted as well. Perhaps in most cases we should not give names directly, saying “whoever is doing this,” and saying that their evil intent be reflected back on them, just in case we’ve identified the wrong people as culprits. But as we’ve seen from the execration texts, the Egyptians were not shy about naming names!

And why the jello mold in the first picture?

In the Bremner-Rhind papyrus execrations from Reidy’s Eternal Egypt, a copper brazier is used to destroy the images of Apep and his servants. The location used for execrations is called the furnace or forge of the coppersmiths. I found this jello mold in a thrift store, and it works nicely for destroying the images of the enemies of Ma’at.

Recommended reading:

The quotes from the tombs of Herymeru and Khentika Ikhekhi are from Texts from the Pyramid Age (Writings from the Ancient World) by Nigel C. Strudwick. You can get it from Book Depository or Amazon.

Magic in Ancient Egypt by Geraldine Pinch has more information on execration and other Egyptian magics. Available from Book Depository or Amazon.

Eternal Egypt by Richard Reidy is also available from Book Depository or Amazon as well.